The Naoshbandiyya may be fairly designated as a universal order. Second in the scope of its expansion only to the Qadiriyya, its adherents are to be found in every region of the Islamic world, with the exception of most parts of Muslim Africa. This ubiquity of the Nagshbandiyya suggests that the order reflects in its character some of the most essential dimensions of the Islamic revelation; and that it is – as has classically been claimed – the path of the Prophet and his Companions, ‘with neither addition nor subtraction. All che Sufi orders maintain, at least in theory, a balance between the exoteric and the esoteric, between sharia and fariga, but none has equalled the Naqshbandiyya in its insistence on rigorous adherence to the shara in practice and on maintaining the absolute primacy of the sharia. This Nagshbandi devotion to the shanta has been of great importance in shaping both its spiritual character and its historical role, not least in Turkey.

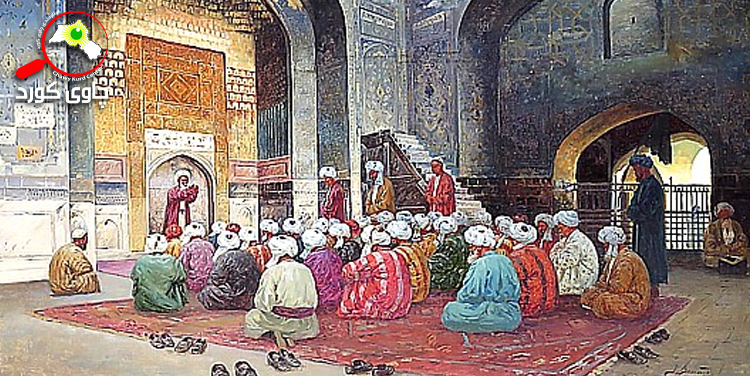

Given this emphasis on observance of sharia, we may further characterise the Naqshbandiyya as a ‘sober’ order, one which eschews the more spectacular practices that have earned fame for other groups, and normatively insists on keeping even the dhiler – the invocation of the supreme name Alläh – silent and confined to the heart. The quality of sobriety and the resultant preference of silent dhilr both stem from Abu Bar, according to the tradition of the order: it is he who stands at the origin of the initiatic line that leads from the Prophet down to Baha’ al-Din Nagshband (d.1389), the eponym of the Naqshbandiyya. The fact of Bakri ancestry, combined with the emergence of the Nagshbandiyya in the broader Islamic world at the time of intense Sunni-Shia rivalry, endowed the Naqshbandiyya with a secondary trait of hostility to Shia Islam. Both these traits traceable to Bakri ancestry – ‘sobriety’ and strong, militant Sunni affiliation – have helped to win the Nagshbanchyya a place of importance in Turkish history. It may be thought that the sobriety of the order appeals well to the sense of decorum, dignity and balance that is so marked a feature of Turkish social and aesthetic norms. As for hostility to Shi’ism, this has obviously complemented the historical biases of the Ottoman polity, and the residual traces of those biases in contemporary Turkey.

The ‘foundation’ of a Sufi order should not be thought of as a formal and deliberate matter, traceable to a given date. Generally one or more generations elapse after the death of the eponym before the particular set of practices associated with him – and to some degree with his predecessors in the initiate chain – crystallise under the impact of some powerful organizing figure into what we call an order. Such a figure mas, for the Nagshbandiyya, Khwaja Ubayclab Ahuar (d1490), who implemented the order’s interest in the sharias by subordinating to his authority two successive Timurid rulers of Central Asia, Aba Said and Sultan Ahanad, and causing them to govern strictly according to his concepts of Islamic law. Equally important, he initiated into the order numerous murids who spread the order out of it Central Arian homeland and laid the foundations of is universal diffusion. Some went south to India and Afghanistan, others east to Mongolia and China, and still ocher west to Iran and more importantly – Turkey.

It was Molla Abdulla Mahi of Simav (d.1490) who, having been initiated into the order in Samargand, was deputed by Ahrar to establish the Nagshbandiyya in Turkey. He founded the first Nagshbandi tekke in Istanbul at the Zeyrek medrese a former church), where he attracted a large following. Partly to escape the pressure of his devotees he migrated to Vardar Yenicesi in Rumelia, where he devoted himself to writing and to the training of disciples who took the order as far north as Sarajevo. The line of succession that he established in Istanbul put forth branches in Bursa, Erzurum and elsewhere, so that in a short time the Nagshbandiyya became widespread through- out both Rumelia and Anatolia.

The connection of Turkey with the Naqshbandi order has been unbroken since the fifteenth century. But the order in Turkey has never taken on national or region- al characteristics; on the contrary, it has maintained vital links with other centres of the order – notably Central Asia and India – and the chains of initiatic descent of Turkish shaykhs are intertwined with those of the Naqshbandi masters from places as far as Sumatra. Two particularly important waves of renewal of the Nagshbandi order in Turkey originated in India. The first derived from the Mujaddid (‘renewer’) of the second Islamic millenium (d.1624). A certain Shaykh Muhammad Murid of Bukhara became the murid of Sirhindi’s son, Khwaja Muhammad Ma/som, and then travelled via the Hijaz, Syria and Anatolia to Istanbul, where he established a Mujaddidi- Naqshbandi tekke on the shores of the Golden Horn.© Numerous disciples then spread the Mujaddidi branch of the order, which seems in its time largely to have displaced most of the existing lines of affiliation.

The second and more important movement of regeneration deriving from India is that associated with Maulana Khalid Baghdad (d.1826), a Kurd from Shahrazur who travelled to India and was initiated into the Nagshbandiyya by Shaykh Ghulam ‘Ali (also known as ‘Abdallah) Dihlavi. Dihlavi was a Mojaddidi, but such is the importance of Maulana Khalid in the order that he is regarded as having originated an independent branch known after him as the Khalidiyya. He retured from Delhi to Sulaymaniye in 1811, but soon left, first for Baghdad and then for Damascus, where he ultimately died of the plague, having initiated a whole host of disciples in the course of the most important movement of Suf renewal in the early 19th century.

Some of Maulana Khalid’s disciples took the Nagshbandiyya to South Bast Asia, the Caucasus and the Crime, but more numerous and important were those who implanted his branch of the order in all regions of Kurdish population and throughout Anatolia and Rumelia. Taha Hakkari, one of his successors, is the spiritual ancestor of the various Kurdish families that have achieved fame in recent times, for deeds religious as well as political, indeed it might almost be said that Kurdish nationalism is a secularized version of the original Khalid impulse. In Istanbul, Maulana Khälid had several followers of importance, including a seyhülislam. Mustafa Asim Efendi, and a whole network of halifes covered Anatolia, the most notable of them being in Konya, Kastamonu, Trabzon, Amasya, Kayseri, Erzurum, Erzincan and Urfa. So complete was the spiritual dominion established in Anatolia by Maulana Khalid – known, like Sirhindi, as a ‘renewer’, although in his case only of a century, not a millennium – that several shaykhs of other branches of the Nagshbandiyya in Anatolia came to him seeking renewed initiation. After Maulana Khälid, in fact, the Khälidiyya is virtually synonymous with the Nagshbandiyya in all of Western Asia.

As ‘renewer’ of the order Maulana Khälid both reemphasised existing features of Nagshbandi practice and introduced new points of emphasis. Rabita – the linking, in the imagination, of the heart of the murid with that of the preceptor – already existed as a prime means of spiritual realization among the Nagshbandis; Maulana Khalid gave it special emphasis, and proclaimed that it was to be practiced exclusively with respect to himself – that is, even after his passing away. This innovation, as well as the rustic Kurdish origins of Maulana Khalid, aroused some opposition among the established shaykh of Istanbul, but appear soon to have been accepted.

Of at least equal interest are the political dimensions of Maulana Khalid’s work. He concludes his treatise on the rabita with a prayer for the well-being of the ‘exalted Outman State, upon which the victorious existence of Islam’ and the defeat and misery of the ‘cursed Christians and apostate Persians’ depends. ID Loyalty to the Ottoman state, viewed as an instrument for the implementation of sharia and the exaltation of Islam, caused the Khälidis to welcome the military reforms of Mahmud I, who repaid their interest by frequently visiting the Selimiye tekke of the Khälidis in Üsküdar. As for the cursed Christians and apostate Persians,’ they were viewed as external enemies to the supremacy of the sharia, in that Christian powers were constantly encroaching on Ottoman territory and Iran continued to show some interest in gaining control of Maulana Khalid’s Kurdish homeland.

The loyalist attitudes of the Khälidis were strained when the successors of Mahmud I moved beyond the measures of military reorganization to a more comprehensive restructuring of the state, significantly distancing themselves from the that’s and inaugurating the process of gradual ‘seculariation’ that found in explicit (if not entirely inevitable) culmination in the foundation of the Turkish republic. The Khalids were involved in a number of movements directed against the seculrising tendencies of the Tanzimat period, including the so-elled Kuleli incident of 1859 and the demonstrations against Sultan Abdülariz in Istanbul in 1876.

In the reign of Sulan Abdülhamit, the Suf orders played a role of considerable importance, both internally and in the implementation of the policy of Pan-kalariam. Among the shaykhs prominently associated with the Sultan was Shaykh Ziya ad-Din Gümüshaneli (d.1894), who was separated from Maulana Khälid by one link in the initiatic chain. He spread the Nagshbandiyya along the Black Sea littoral, and enlisted with his murids to fight in the Russo-Ottoman war of 1877. Most of the shaykhs associated with Sultan Abdülhamit were, however, drawn from orders more widely represented in the Arab lands than the Nagshbandiyya, such as the Rifa’iya and the Shadhiliya, and the Nagshbandis were not uniformly in favour with him; the celebrated Shaykh Muhammad As’ad was banished by the Sultan from Istanbul to Ibril, for reasons unknown.

Relations between the Young Turks and the Sufi orders have not, to my knowledge, been adequately examined. It is possible that Nagshbandi cousels were divided on the overthrow of Sultan Abdülhamit, although by 1910 the German orientalist, Martin Hartmann, described the political attitudes of the Nagshbandis as uniformly ‘reactionary’. What is certain is that, irrespective of their political attitudes, the Khälidi Nagshbandis were the largest and most influential Sufi order during the twilight decades of the Ottoman State: in Istanbul alone, they had over 60 tekkes, more than any other order,.

After the Ottoman collapse, an important number of Naqshbandi shaykhs participated in the liberation struggle, which was in its origin conceived as jihad, with the purpose of restoring Islamic sovereignty on liberated Muslim territory.

Particularly well-known is the role of At Efendi, shaykh at the Ozbekler rekke in Usküdar, who gave refuge in the tekke to various persons sought by the allied police in Istanbul; Ismet Inonü himself stayed there at one point. Hasan Fevzi Efendi of Erzincan volunteered with his followers to join the war, and he later represented Erzincan in the first National Assembly that met in Ankara. Even two individuals that are execrated in the official historiography of the Turkish Republic, Seyh San and Seyh Mehmet Esat, lent their support to the struggle. The former was one of the principal forces of the founding of the Müdafa-i Hukuk Cemuyet,! and the latter, at his residence in Erenkoy, played a role similar to that of Ata Efend in Uskudar: among those who came to seek his blessings was Ferzi Cakmak.

The new Turkish state that these Nagshbandis – together with numerous other men of religion, both ulama’ and shaykhs – had helped to create was destined, however, to embark on a policy of radical hostility to Islam that the official slogan of secularism has never been able to conceal. For secularism must surely mean the separation of the religious and political spheres, with both enjoying autonomy, and perhaps a degree of general supervisory competence vested in the political authority. “Secularism’ in its Turkish application has meant, however, the dominance of an arbitrarily circumscribed religious sphere by an enlarged authority of an aggressively irreligious state.

It was not simply that the Turkish Republic decided to divest the state of the last vestiges of fealty to the sharia and to subsitute for it various codes of European origin; it wished to supplant Islam as a dominant socio-cultural force and therefore interfered massively and coercively, in matters of worship and religious education. It is in this framework of general hostility to religious traditions and institutions that the proscription of the Suf orders must be placed. True, the proscription came in September 1925, after che suppression of the revolt of Seyh Sait of Palu, but that revolt was, at the most, the pretext for the measure. It would always have been possible to move selectively against certain individuals or orders, but this was not done (although different degrees of severity have been observable in the application of the law).

One of the remarkable features of the rebellion of Seyh Sait, well brought out by Martin van Bruinessen, 21 is the relatively restricted scope it enjoyed. Not all Nagshbandi shaykhs (even in Kurdish-populated parts of Anatolia) gave it their support, and there seems to have been little if any active Turkish participation. It was precisely the overwhelmingly Kurdish participation in the revolt that made it, malgré soi, almost as much a Kurdish movement as an Islamic jihad, which it proclaimed itself to be. It is significant that ambiguities surround this, the sole – and this is a point worth stressing – incident of Nagshbandi armed resistance to the republican order. Indeed. When reviewing the history of the Nagshbandiyya in Turkey over the past fifty years, it becomes difficult to explain the horror expressed by the devrim yobazlan at religious “reaction’ in general and Nagshbandi reaction’ in particular, unless it be a case of bad conscience on their part. For what is remarkable about the Nagshbandis and other supposedly militant groups has been their relative passivity and failure to mount determined resistance to the anti-Islamic order.

The law of September 1925 banning the Sufi orders confidently stated that from this day forth, there are no tanikats, or dervishes and murids belonging to them, within the boundaries of the Turkish Republic, ’23 What resulted, of course, was not the total disappearance of the orders, but the closure of the tekkes, the most external manifestation of the orders and not the core of their existence Gradually this was perceived and other measures – arbitrary arrest, execution, banishment, etc. – were undertaken to bring to an end the existence of the orders, particularly the Nagshbandiyya. In 1930, the chairman of the National Assembly found himself declaring “The Naghbandi order is a make we have been unable to crush,

It was in December 1930 that the notorious Menemen incident took place, celebrated in the historical mythology of the Turkish Republic as an archetypal clash between the fences of enlightenment and dark reaction. The evidence suggest rather that the incident was exploited, and possibly even staged, by lamet Indmii as a pretext for the atainment of certin political purposa and the arrest and killing of Serh Mehme: Saad, the foremost Nagibbandi shaykh of Istanbul in the fir decade of the republic. On 23 December 1930, a certain Dervi; Mehmet atterpted to rouse the people of Menemen in revolt, proclaiming himself the Mahdi and beheading a young officer who attempted to restrain-him. No link was ever shown to exist between Derviq Mehmed and Seyh Mehmet Eat, but the Seyh was arrested, together with many other Nagshbandis from Istanbul, and brought to Menemen for trial. Among those sent to the gallows was Seyh Mchmer Esat’s eldest son, and the Seyh himself was poisoned in the prison hospital (at least according to the plausible suspicions of some of his surviving followers).

This tragedy did not bring the spiritual influence of Seyh Mehmet Eat to an end. Among his numerous halifes have been men that wielded great influence, exercising a form of religious authority that transcended the limits of their immediate following. Among those who have died in recent years can be mentioned Hali Efendi of Düzce, Nuri Efendi of Saner, Hulusi Efendi of Beykoz and Muhittin Efendi of Bolu. There are surviving Halies in Yozgat and Balikesir.

The most important and widely respected successor of Seyh Mehmet Esat was the late Mahmut Sami Ramazanoglu, known to his following as Sami Efendi. By formal training he was a lawyer, but more importantly he was generally acknowledged as a figure of great piety and learning. Unlike other influential shaykhs of Istanbul who have exercised their functions in a semi-public manner through presiding over mosques where their following congregates, Sami Efendi lived somewhat as a recluse at his house in Erenköy, discreetly receiving there small groups of followers. This did not prevent him from attracting an extremely wide following, as would become appar- ent every year on the Hajj: with the constraints of ‘secularism’ left behind in Turkey, many thousands of pilgrims would cluster round Sami Efendi to pray behind him and receive his blessing His fame and following also extended beyond the frontiers of Turkey, to Bosnia and Syna. He migrated to the Hijaz in 1979 in order to spend the remaining years of his life in traditional fashion as a mujawir in Medina, and he died there on February 12, 1984, Musa Topbas succeeded hum as leader of this particular Nagshbandi congregation, although not without some internal dissent. The journal Alunoluk serves as its organ; while not averse to socio-political comment, it mainly concentrates on the moral and spiritual advancement of the individual as primary imperative.

It is not possible to list here all the hardy lines of Khalidi tradition that have survived the rigours of the republican period; we will content ourselves with a few. First, a line originally associated with Daghistani refugees, instituted by Abu Mehmet Medeni (d. 1913), who made his way to Turkey after escaping from captivity in Siberia and built a village, centered on a reel, in the mountains bchind Yalova. His successor, Serafeddin Zeinelabidin, was born in Daghistan in 1876 and later joined his master in Turkey. In the War of Liberation, the village and the rekke were destroyed by the Greeks, and after the proscription of the Sufi orders, Serafeddin suffered a period of imprisonment in Eskisehir, where he was a fellow-inmate of the celebrated Said Nursi.

Nonetheless, the Daghistani branch of the Khälidi Nagshbandis in Turkey survived. Serafeddin, who died in 1936, had two principal successors: Abdullah Daghistani, who settled in Damascus, where his own successor, Shaykh Nazim Qubrusi, now heads a subgroup of the order that has adherents in Turkey as well as Syria, Lebanon and Cyprus, and Mehmet Necati Efendi, who spent most of his life in Bursa. The principal successor of Mehmet Necati Efendi is a remarkable man who has undertaken to revive the example of Abu Mehret Medeni in the contemporary world: the foundation of a Nagshbandi village, near Ankara, grouped around a teleke and the residence of the shaykh. Some followers of the shaykh till the lands around the village, while others, whose professions range from judge to menial labourer, commute to Ankara.

A number of other lines have descended from Shaykh Zia ad-Din Gümüshaneli, mentioned above. One terminated in Seyh Abdulhayy of Besiktas (d. 1957), who functioned as imam at the Yahya Efendi mosque and appears to have led a relatively tranquil life. He died without appointing a successor.

A more important and better-known branch of the Gümushanch line is that which included the late Mehmet Zahit Efendi (Mehmet Zahit Kotku), imam of the Iskender Pasa mosque in the Fatih district of Istanbul, who died on November 13th, 1980 His immediate predecessor, Abdulaziz Efendi, had already attempted to counteract the tendencies of the age by addressing himself to the university-educated youth and trying to enlighten them on Islam; this Mehmet Zahit Efendi did with greater success. The mosque over which he presided became in the late 1960s a centre for those who were dissatisfied with the meager intellectual and spiritual fare offered them by establishment ideology and wished to find their way to a living embodiment of Islamic tradition, It has continued to fulfill this function oven after the death of Mehmet Zahit Efendi. Students and university professors, as well as members of the bureaucracy and professions, comprised the majority of Mehmet Zahit Blendi congregation.

HAMID ALGAR