Particularly important among the associates of Mehract Zahit Efendi were leading figures of figures of the Milli Selamet Partid: Necmettin Erbakan, Hazan Aksay, Korkut Öal and Rehmi Adak. This led several observers to regard Mehmet Zahit Efendi as the hidden hand’ behind the party, 33 and others to treat the internal disputes of the party as struggles between Naguhbandi and Nurcu factions,34 But Erbakan denied that the MSP was a tarikar party, and it is far from certain that Mehret Zahit Efendi approved all the political maneuvers in which Erbakan engaged, particulady his shifting coalitions. Indeed, on January 10, 1970, Mehmet Zahit Efendi said in the hearing of chis writer that Muslim participation in politics was a mistake, and that under present conditions in Turkey any attempt to restore Islamic political authority would lead to bloodshed with no guarantees of a successful outcome. Instead, it was best to reconstruct Islamic society “unofficially’ in such a way that an Islamic state would ultimately and inevitably emerge from it.

Nonetheless, the MSP – at least in its original conception – can be seen as a political adjunct to this social process, which certainly does not exclude actions with political overtones. Mehmet Zahit Efendi used to advise his followers, for example, to shun imported goods as far as possible, particularly in food and clothing. Mehmet Zahit Efendi was succeeded at the Iskender Paça mosque by his son-in-law, Esat Coçan, formerly a professor at the Faculty of Theology in Ankara. The influence and extent of this Nagshbandi group has somewhat declined during his tenure, not least because of tensions with Necmettin Erbakan that began coming to the surface in early 1990. The successful resuscitation of the Mill Selamet Partisi, after a period of military- imposed proscription, under the name of Refah Partisi, seems to have inspired Erbakan with a degree of self-assurance that prevents him from granting Est Coçan the same degree of deference that he had extended to Zahit Efendi, there are even hints that Erbakan aspires to the religious as well as political leadership of Turkish Muslims.

One indicator of the diminished, although still considerable, influence of Esat Cogan is the reduced circulation of the magazine Islam, published under Luis auspices, once one of the most widely read of all Turkish periodicals.

The funeral of Mehmet Zahir Efendi (which was attended by over 30,000 people) was presided over by another Naqshbandi shaykh of Istanbul, Mehmet Efendi, imam of the Ismail Aga mosque in Cargamba. A native of Of, a region of the Black Sea littoral celebrated for its conservative religiosity, Mahmud Efendi is the hale of Ali Haydar Ahishevi (d. 1960) who, after a brilliant scholarly career in the final years of the Ottoman State, devoted the remainder of his life to the unobtrusive training of thousands of muds, interrupted only by periods of imprisonment, 36 Certain activist Muslims reproach Mehmet Efendi with a concentration on apparently mitor outward details, such as men growing full beards and women donning the caraf His followers, however, regard this determination to maintain an outward appearance that defies the criteria of the Turkish Republic as an important mean of culavating Idlamic identity. Because of this emphasis on visible adberence to the that’ as the basic element of the Nagshbandi path, as well as the primacy of oral teaching and personal contact, Mehmet Efendi had, until recently, refrained from the writing of books, At present, however, according to his disciples in Istanbul, he is currently engaged on a multi-volume kaftr of the Quran.

Many of the shaykhs mentioned above have had a following that extended across Turkey, and appointed halies to act on their behalf in various cities. Other Nagshbandi shaykhs of the republican period have had a more restricted sphere of influence – a city and its environs, or sometimes a province. Such was the case with Seyh Ismail of Sivas (d. 1960; according to some, he left no halife; according to others, his successor is Seyh Hamit of Darende) and Seyh Muhammat Lüthi of Erzurum (4.1956 without appointing a successor). 37 The numerous Nagshbandi shaykhs of the Kurdish areas of Anatolia also fall into the category of shaykh whose influence is regionally defined, although some have enjoyed considerable fame in Kurdish areas beyond the frontiers of Turkey. Of particular importance have been Seyh Ziyaettin Nursini (Hazret-i Nursin) and his descendants, Molla Mehmet Emin and Seyh Taha; Seyh Ahmet Hiznavi, who fled Turkey after the proscription of the Sufi orders but appointed a number of halifes there; and Seyh Sait Seyfettin of Cizres (d. 1971) and his son Nurullah. There are also Kurdish shaykhs of the order in Mutki, Van, Diyarbakir and Hakkari. The relative multiplicity of shaykh in the Kurdish areas is no doubt due to the particular and lasting impact of Maulana Khälid on his fellow Kurds, as well as to the less rigorous enforcement of anti-farikat measures in the east and south-east of Turkey (this, for various reasons).

A Kurdish shaykh who attained wide fame throughout Turkey in the 1980s was Resit Efendi of Adyaman, whose father; Abdulhekim Efendi had been one of the main halifes in Turkey of Seyh Ahmed Hiznavi. Ragit Efendi was reputedly able to impel the profligate to a life of virtue merely by casting his gaze upon them, and chis gift of instant moral reformation would draw thousands of people flocking to Adiyaman.40 On the one hand, this success led some other Naqshbandis to reproach him with ignoring the formalities of initiation, and on the other hand, it impelled the authorities to banish him to Canakkale on August 19, 1983, invoking undefined ‘offences against national security and public order’ as justifying pretext. 41 When the Cow of devotes simply diverted itself from Adiyaman to Canakkale, he was put on the nearby island of Imroz and rendered incommunicado. This period of banishment in no wise diminished his appeal. Fie died on October 22, 1993, and was sudeceded by a number of halifes active in various parts of Turkey, including Istanbul, Some other Naqshbandis reproach Ragit Efendi with ignoring the formalities of initiation into the order and with misinterpreting the practice of rabita.

Another expression of the continuing Naquhbandi presence in modera Turkey has been the emergence of what we can only call sect” from the followers of two shaykhs: Sileyman Bfendi Tunaban (d. 1959) and Abdülhekim Arvai (d 1943), We use the word sect for two reason: fine, because the shaykhs in question died without appointing halifes in the traditional sense, so that the continued existence of a congregation devoted to them after their death cannot be thought of as a simple prolongation of heir line: second, because they or their close associates introduced new points of emphasis that were elevated to a point of doctrinal centrality and became the occasion for polemics with other groups.

Süleyman Hilmi Tunahan was born in Silistre in 1888, but studied in Istanbul, graduating as a kod from Sülleymaniye medrese. After the virtual cessation of religious instruction in the frst two decades of the republic, Süleyman Efendi cook it upon himself to build up a network of Qur’anic instruction in various parts of Anatolia, This earned him two prison sentences, in 1939 and 1944. In 1957, the government tried a replay of the Menemen scenario: an unknown person proclaimed himself Mehdi at the Ulu Cami in Bursa, and Süleyman Efendi was arrested as the alleged planner of the incident. He was released from prison after several months, and died on September 16, 1959.

Leadership of his following after his death was assumed by his son-in-law, Kemal Kaçar, sometime parliamentary deputy from Kütahya, who continued the work of the Qur’änic schools and extended them throughout Anatolia. These schools were a subject of controversy, not least because they existed in deliberate competition with the far less numerous, state-sponsored imam-hatip okullan, which were felt to be giving instruction in a truncated version of Islam, one which implicitly accepted the thesis of secularism. In addition, certain claims were put forward concerning the spiritual rank of Süleyman Hilmi: he was said to have had vested in him ‘the heritage of prophet- hood’ (veraset-i-nubuvvet) and ‘the spiritual direction of the age’ (asnmzin tasamifu). Further, like Maulana Khälid before him, he gave instructions for rabita to be practised exclusively with reference to him, something which gave rise to probably unfounded rumors that his followers always look at photographs of him before making their prayers. He is held by his followers to be ‘the seal of the evliya”, i.e. to have brought sainthood to an end; it is, therefore, only through him that access may be had to the secrets and riches of the Nagshbandi path, so that all claimants to shaykh-hood in the present age stand revealed as conscious or unconscious frauds.

A similar view that the bereket (Ar. baraka), the sacred force, of the Nagshbandi tradition has been exhausted, so that all chat remains to be done is to fix one’s gaze on the final representative of the line, characterises the second sect, the lakelar, named after Hüseyin Milmi Isik, a murid of Seyh Abdulhekim Arvasi. Arvasi came from a Kurdish family of a long-standing Suf and ‘alim tradition; his ancestors had been Qadiri for many generations, but like many other Kurdish shaykhly families switched its affiliations to the Nagshbandiyya soon after the appearance of Maulana Khalid, He came to Istanbul in 1919 and was appointed postrisin at the Murtaza Efendi (also known as Kasgari) tekle near Byüp, a Nagshbandi foundation. The rekke drew to it many devotees, and even after it was closed, his followers still sought out Arvasi in his nearby home. He was twice arrested, first in 1925 and then in 1933, and in 1943 he was banished to Izmir, where he spent the few remaining months of his life. Dying the same year, he was buried in the village of Baglum near Ankara.

Abdülhekim Arvasi’s emphasis was on the maintenance of strict Sunni belief. He waged polemical battles not only against the ‘secularism’ of the republic, but also against Shi’ism, Wahhabism, the so-called Salafi school of Afghani and ‘Abduh, and any manifestation of what was rather broadly called reformism’ (reformluk).

This narrowly conservative position involved an elevation of chl-i sunnet ulemasi (the classical scholars of Sunni Islam) and their works to a position of unquestionable authority and eternal adequacy; here it is fully justified to speak of an orientation to the past. This orientation is strengthened by the conviction that the Nagshbandi line has virtually come to an end, that – as Isik put it to the present writer – the light of the Prophet had shone brightly for a thousand years; its gleam was then restored somewhat by Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi, but again it is failing without any renewer in sight. ” What is left to do is then to study the works of past ‘ulama’ as if they were sacred texts; to conduct polemics with all who fall short of the like definition of Sunni orthodoxy: and to glorify the memory of Abdulhekim Arvasi.

We see then, that the Nagshbandi order has manifestly survived in Turkey, in various areas and with varying degrees of vitality. The simple fact of survival – whether of the Nagshbandiyya or of Islamic religiosity and fervour in general – is hardly sur- prising, although many western analyses seem to find it so. The millenial association of the Turks with Islam could hardly have been expunged by fifty years of somewhat mediocre, elitist government, and the Sufi orders, as a cardinal element in traditional Turkish religious life, were in fact bound to survive their prosenpton This survival cannot be regarded as the result of an identity crisis or as the reaction of naive and simplistic souls to the complexities of modernisation’,48 Nor is it to be regarded as the epiphenomenon of given socio-economic developments: the Suti orders are to be found in cities, towns and villages, and their members are recruited from both rich and poor, educated and illiterate, so that they fulfil an integrative role in a highly fragmented society.

What is more important than registering the mere fact of survival is to indicate, first, the relative success of the Nagshbandiyya among other Sufi orders in surviving the proscription, and second, the nature and significance of the survival.

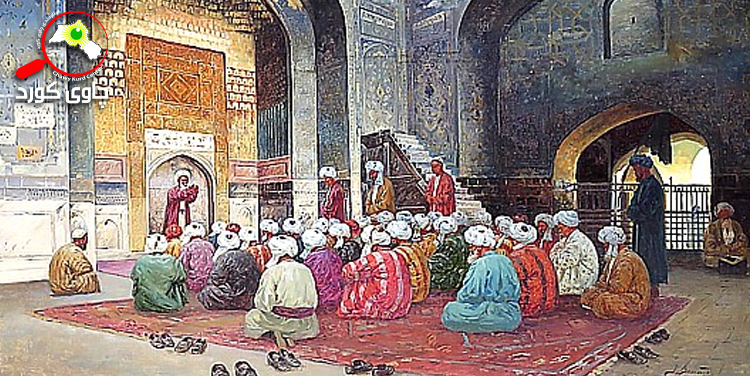

There can be no doubt that the Khalid Naqubbandis have withstood the pressures of the republican period more successfully than any other tarikat. Kadiris, Halvetis, Rif’is and Meylevis also exist, but in far smaller numbers, and a sure indica- tion of the greater importance of the Nagshbandis is that they have borne the brunt of anti-Suf persecution in the republican period. Small items regularly appear in the press reporting that in a given place, Nagshbandis have been surprised while performing their devotions and arrested as if they were a dangerous ring of conspirators. This primacy among the Sufi orders is due not only to the quantitatively superior position of the Nagshbandis at the onset of the republican period. As already remarked, the proscription of the tarikats was most effective in bringing to an end – almost univer- sally – the life of the telkes. The Naqshbandis, however, were particularly able to dispense with rekkes: performing neither the ritual dance of the Mevlevis nor the spectacular feats of the Rifa” is, they have had no essential need for a ritual structure in which to perform the silent dhiler that is their central and distinctive practice.

Silent dhiler in itself favours anonymity and invisibility: Jami (d.1492) defined the ideal state of the one performing the Nagshbandi dhiler to be total engrossment in the dhiler without his neighbor being aware of his state. As for the second pillar of Naqshbandi devotional practice, sober (keeping the pious company of the shaykh and benefiting from his presence and pronouncements), this is attainable, with due circumspection, in mosques and private residences. The same holds true of recitation of the traditional Nagshbandi litany, khatm-i khudjagän.

But what is the content of the Nagshbandi survival? What has persisted of the original Khalid impulse, the militant fervour to establish and maintain the supremacy of the shari’e? For that matter, is the degree of learning in the sciences of the sharia now prevailing among Nagshbandi shaykh the same that it was a century ago?

In answering these questions, we must clearly spcak of a decline. It is not that piety has lessened, or that shaykh are unable to advance their disciples on the path to direct perception of spiritual truth and fixing permanently on their hearts an impress of the divine name – which is, after all, the ultimate goal of the Nagshbandi path. The decline is rather in the twin spheres of learning and socio-political activity. After the destruction of religious education in the early part of the republican period, many Nagshbandi shaykhs assumed the task of maintaining Islamic learning in Turkey. Whereas the class of ulamä’ could be dissolved with great ease by the state to which it had always been ted, the tankets, with their autonomy and closeness to the people, were a different matter, (A similar developmenc is visible in the Soviet Union; there, too, the tankas – again, especially the Naqshbandiyya – have tried to fill the gap left by the abolition of the medreses )

But there has been little Nachwnchs in this transmission of religious learning: tradition has been maintained, but in very attenuated form. It is an inescapable fact that barely a single major work in the Islamic religious sciences has been written by Nagshbandis in the republican period. Here, of course, Naghbandis have shared che fate of the Turkish Muslim community of which they form a part; Kemaliam may not have killed Islamic learning in Turkey, but it certainly seems to have crippled it.

As for militant Nagshbandi opposition to the political and ideological bases of the republic, this has been extremely rare. It would be more correct – especially for: the first forty or so years of the republic – to speak of a tenacious, passive resistance, a desire to maintain oases of Islamic awareness and practice in the wasteland of Kemalism, with only occasional and somewhat timid attempts to extend the area of cultivation. The political involvement of groups such as the Säleymancilar and isikalar, whatever be their private views concerning the founder of the Turkish Republic and its ideology, has been restricted to delivering bloc votes at each election, first to the Justice Party and then to the Anavatan (Motherland) Party founded by Turgut Özal. As for the Milli Selamer Partisi, (which may be regarded, with certain qualifications, as having started as a Nagshbandi venture), and its ever more popular successor, the Refah Partisi, there are grounds for regarding them as an integral, although still contested part of the existing political structure. As a matter of course, Erbakan and all members of parliament are obliged to swear allegiance to a constitution that still mandates ‘secu- larism’ and to participate in various ceremonies at the mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal. As if this were not enough, Erbakan once suggested that if the founder of the Turkish Republic were still alive, he would enroll in the Refah Partisi, and he has even remarked that it is not the principle of secularism that he and his party find objectionable, but the mode of its implementation. Such utterances may, of course, be tactically inspired, but it is difficult to be certain.

This incipient integration of the Real Partisi into the political structures of the Turkish Republic – which may be crowned before long by the accession of Erbakan to the premiership – has of course been facilitated by the loosening of certain Kemalist restrictions. Arrests of Naqshbandis for holding devotional meetings appear to be a thing of the past, and the continued existence of the order is an accepted – although still widely misunderstood and misinterpreted – fact for all bur the most recalcitrant segments of secularist opinion. It thus required no particular daring on the part of Eyüp Agik, then secretary-general of the Anavatan Partisi, to declare openly in May 1988, * am a Naqshbandi. *53 It was likewise a sign of the tmes that several Nagshbandi shaykhs were in prominent attendance at the funeral of Prime Minister Turgut Ozal in April 1993.

It is precisely this growing openness of Turkish society, with the concomitant expansion and diversification of Islamic awareness and expression, that seems likely to erode the role of the Nagshbandiyya (and a priori that of the other Suf orders) Turkey has now what is probably che most hvely and variegated range of Islamic publications anywhere in the Muslim world: four daily newspapers, a host of weekly and monthly periodicals dealing with current events, quarterly journals dealing with theoretical and philosophical questions, new editions of classical texts, a flood of translations from Arabic, Persian, English and French, studies of the Ottoman and Islamic past, and – not least – the works of contemporary Turkish Muslim intellectuals beholden to no par- ticular tradition or school of thought. It is unlikely that the voice of the Nagshbandi shaykhs – in many cases an uncertain and hesitant one – should come to prevail over this multiplicity of claims to Islamic authenticity, and far more probable that the order will attract only those who who are temperamentally drawn to the devotional core of traditional Sufi practice. If this be the case, the Nagshbandi order will be seen to have functioned primarily as a bridge between the Ottoman period and the ongoing Islamic revival in Turkey – in itself a substantial and creditable achievement.