Royal Air Force Air Historical Branch

The RAF, Small Wars and Insurgencies in the Middle East, 1919 – 1939

“Map of IRAQ”

Northern Iraq

The primary British focus in Iraq in the early 1920s was on the mountainous northern region of Kurdistan, bordering Turkey and Persia (now Iran), where it was necessary to confront the simultaneous threats posed by Turkish territorial ambitions and Kurdish separatism, which had the potential to destabilize other areas of Iraq. The resulting operations, beginning in February 1923, were very fully described by the Air Officer Commanding (AOC), Air Vice-Marshal Sir John Salmond, in the London Gazette – an entirely open publication. Salmond did not make extravagant claims to the effect that British aims were pursued via independent air action. ‘I considered,’ he wrote, ‘that a combined air and ground operation should be used to attain my two fold objective’.

Salmond’s plans were drawn up in consultation with his senior Army subordinates and with the responsible political authorities. He elected to form two separate brigade-sized columns, one (‘Koicol’) consisting of British and Indian troops, the other (‘Frontier col’) comprising Iraqi Levies. Koicol was sent from Mosul to Koi Sanjak, which faced the most immediate threat from the combined action of Turkish irregulars and the followers of the Kurdish Sheikh Mahmoud. Frontier col was dispatched to Rowanduz to block Turkish infiltration

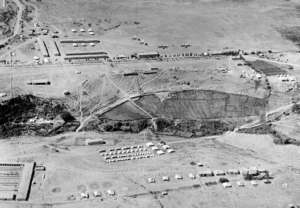

via the Persian frontier, which offered the only snow-free route into Iraq during the winter months (see Map 3). Air support for the two forces (both of which were equipped with RAF mobile pack radio sets) was provided by three squadrons operating from Mosul, while a fourth flying from Kirkuk targeted Mahmoud and his followers in the hills in the Surdash district, to the north of Sulaimaniyah.

As in Somaliland, the most notable features of the air operations in northern Iraq at this time were their variety and (by the standards of the day) their sophistication. Independent air operations were mounted against Mahmoud and his supporters for much of this period, primarily because they were located in remote and mountainous territory well beyond the reach of Salmond’s ground troops. In his view, these attacks played an important part in deterring local tribes from rallying to Mahmoud’s support, but he never at any point suggested that this had been the decisive factor in the insurgents’ defeat.

Elsewhere in his dispatch, he described how the need to project force rapidly into the region at an early stage in the crisis persuaded him to airlift two companies of the 14th Sikhs to Kirkuk. Before his two columns set out on their respective missions, potentially hostile tribes along their route were deluged with air – dropped proclamations bearing the seal of an influential local dignitary exhorting them not to hinder the British advance. After ground operations began, air reconnaissance helped to identify the key area of enemy resistance along the Levies’ route from Irbil to Rowanduz, and Salmond was able to perform his own personal reconnaissance of the area – a ridge of hills known as the Spilik Dagh. ‘During this flight,’ he wrote, I was very much impressed with the natural strength of the Spilik position, and, knowing at the same time that the enemy were holding it in force I formed the conclusion that without an enveloping movement it could not be taken without considerable loss.

Essentially, Salmond had in his possession a view of the future battle area that would not have been available to earlier British commanders in Iraq, and this enabled him to deploy his quite limited ground forces effectively and economically. Aircraft furthermore provided the means by which the actions of the two columns could be quickly and easily co-ordinated, either through message dropping or pick-up, or by actual landings at forward locations to allow senior officers – Salmond included – to discuss progress and plans. On 15 April Salmond directed Koicol to conduct an enveloping action from the southeast of the Spilik, threatening to cut off the Turks by blocking any potential retreat back towards Rowanduz. Frontiercol were to continue their advance from the south -west in the meantime, pinning the enemy in position. Subsequently, the two columns were to link up before launching a co-ordinated assault on the Spilik.

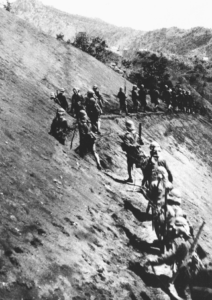

Of the two forces, Koicol faced the more challenging task in the form of an advance north through exceptionally difficult terrain – rugged hills, ridges, and ravines – along a route dominated by the surrounding high ground and limited in places to only the most narrow defile. All the advantages should have belonged to the defenders and yet, having set out on 17 April, Koicol reached the projected rendezvous point just two days later. A major factor in the rapidity of their movement was the combined exploitation of air reconnaissance and air presence – an effective substitute for the picketing operations that would otherwise have had to be undertaken by the ground troops themselves, at considerable cost in both time and resources. On the morning of the 19th, the Turks made their stand, Koicol coming under fire from prepared defensive positions in the hills all around them. But the column suffered just five casualties

(all wounded), whereas their adversaries left behind thirty dead when they retired after some three hours fighting. Aircraft co-operated most effectively throughout the engagement; the enemy in sangars and trenches were bombed and machine gunned; messages were dropped on the Column indicating concealed positions which were occupied by the enemy.

With Koicol now threatening to block their escape route from the Spilik, the Turks were left with no option but to withdraw, and Frontiercol moved into the area unopposed on the 20th. Salmond expected to meet further resistance during the final march to Rowanduz, but both air reconnaissance and human intelligence (HUMINT) indicated on the 21st that the Turks had evacuated the town, and that the main approaches from the south were also clear. It was learnt soon afterwards that they had crossed the border into Persia and had there been disarmed by the Persian military authorities.

Salmond could now turn his attention to Sheikh Mahmoud, whose main support lay in southern Kurdistan between Sulaimaniya and Surdash. Koicol was withdrawn to Kirkuk, re-equipped and assigned three fresh battalions. In the meantime, proclamations declaring that government troops were soon to occupy Sulaimaniya were dropped right across Mahmoud’s main area of influence, and independent air operations were mounted against the villages inhabited by his forces. The new column set out from Kirkuk on 12 May, the general expectation being that Mahmoud would seek to halt them at the Bazian Pass – the only gateway through the Qara Dagh hills, which shielded Sulaimaniya, and another perfect defensive position (see Map 4). Plans were prepared for combined ground and air operations to seize the pass, but air reconnaissance on the 14th suggested that Mahmoud had not had time to prepare defenses in the area, and also confirmed the presence of a water source near the pass. The assault plan was therefore cancelled, and the column instead embarked on a forced march of 21 miles to this location. An advance guard was then sent forward to establish a presence in and around the pass.

Only a single range of hills dissected by the Tasluja Pass now lay between the column and Sulaimaniya. On the 15th, further intelligence reporting the presence of enemy horsemen at the pass led the column commander to order a second forced march, which was equally successful. Captured correspondence afterwards confirmed that Mahmoud had intended to hold the pass, but his ambitions had been thwarted by the rapidity of the column’s advance; they covered 43 miles in two days. That evening, leaflets were dropped into Sulaimaniya ordering local notables out to meet the column, but a number of Mahmoud’s supporters escaped during the night, and the air patrols sent out to find them were largely frustrated by poor weather. The column entered Sulaimaniya unopposed on the 16th. Salmond then described how they had afterwards moved north into more rugged and mountainous terrain to complete the task of eliminating Mahmoud’s power base.

It now remained to break up the semi-military organization which Sheikh Mahmoud had created in the Surdash – Mirgah area, to turn out his own forces from the villages in which they were established, and to impress those Pishder and Shilanar districts which he had chosen for his stronghold … Independent air operations against Sheikh Mahmoud were continued throughout this period, and, backed up by the rapid movement of the column, allowed him no chance to organize resistance or to check the disintegration which had at this time seriously depleted the strength of his own irregular forces.

In the execution of these missions, both air and ground forces were careful to discriminate between friendly and hostile elements. As Salmond put it, ‘no villages were touched other than those of the Shilanar tribes above-mentioned which had probably above all others been consistently and actively hostile to the government. Inhabitants of other villages were allowed to return and continue their cultivation.’ On the 25th, news was received that Mahmoud had fled across the border into Persia.

The full range of air operations conducted in support of this campaign encompassed attack, close air support, interdiction, reconnaissance, air presence, leafleting and air transport, which itself comprised communications, personnel movement, re-supply by both dropping and landing, and casualty and medical evacuation. It is impossible to gauge the impact of the many independent air strikes directed primarily against Mahmoud and his followers between February and May 1923, but it seems very improbable that they were not a significant factor in the relative ease with which his forces were defeated.

On the other hand, there are a number of ways in which the application of air power demonstrably allowed ground operations to be executed more rapidly and economically than in the past. Intelligence disclosing that a particular route or pass was not held by the enemy had truly far-reaching implications for the way in which ground troops were deployed. It provided a basis for fast and aggressive movement, without the precautionary employment of advance guards, patrols and pickets. Air reconnaissance also helped to pinpoint enemy habitations spread across broad expanses of remote country, which could only have been covered by very large and costly ground expeditions, and gave Army commanders a wealth of very valuable tactical information about their adversaries, which contributed much to their ultimate defeat. Offensive air power reduced the need for ground formations to deploy as much organic fire support as they had in the past, while airborne communication enabled geographically separate formations to operate in a mutually supporting manner – a decisive factor in the capture of Rowanduz.

Whether air power could or would have been so effectively and comprehensively exploited in the absence of overall RAF command of British forces in Iraq can only be a matter for conjecture, but considerable professional

air input would at the very least have been required at the most senior command levels to realize the true potential of the air medium. Predictably enough, in his dispatch, Salmond was keen to highlight the contribution of air power in these operations. ‘Throughout their course’, he wrote, I was particularly pressed by the many and particular advantages which the informed use of air power had given me for conducting this kind of warfare.’ But he did not make the mistake of claiming all the credit for the RAF, and he paid particular tribute to the commander of Koicol, Colonel Commandant B. Vincent. It was undoubtedly due largely to his strenuous and determined personality and military skill, and to the hard marching by which he thrust his column rapidly forward through every obstacle and difficulty, that Rowanduz was occupied without any serious loss to either column … In the Sulimani operations, by the rapidity of his movement, he carried two strong positions before the enemy had time to concentrate, and consequently upset his plans.1

Neither Sheikh Mahmoud’s insurgency nor the Turkish challenge were eliminated by the British campaign of 1923, but the Turks suspended their territorial claims after they were again defeated in the following year, and a formal treaty settled Anglo-Turkish differences in the region in 1926. By contrast, attempts to establish a new civil administration in Sulaimaniya following the withdrawal of Koicol in June 1923 ended in failure, and Mahmoud afterwards returned from Persia to resume his activities. However, the twin threats which Salmond had confronted – that Mahmoud would draw in the Turks or precipitate unrest in other areas of Iraq – steadily declined in severity, and he was effectively contained in a small area of Kurdistan by combined ground and air operations.

In 1927 he was decisively defeated and compelled to leave Iraq. Following the end of the British mandate in 1930 he again sought to mobilize his supporters in southern Kurdistan, and an Iraqi Army force backed by four RAF squadrons then resumed operations against him. He finally surrendered in May 1931.2

Notes

1 This section is based on Salmond’s report in the Supplement to the London Gazette, 10 June 1924.

2 CD 92, Report on the Operations in Southern Kurdistan against Shaikh Mahmoud, October 1930-May 1931, Air Ministry, April 1932 (AHB copy). This report contains a useful biographical note on Mahmoud by one Captain V. Holt, the Oriental Secretary to the High Commissioner of Iraq.