Since the first Kurdish newspaper, “Kurdistan,” was published in 1898 under the editorship of Miqdad Medhat Bedirkhan—releasing only 31 issues over four years—both the concept of journalism and the profession itself have undergone profound transformations. Yet, one thing has remained constant: the intrinsic link between journalism and the principles of speaking truth to power, criticizing authority, and exposing the shortcomings and corruption within governments and societies. Despite the advancements of the digital age and artificial intelligence, journalists have not been freed from the dangers inherent to their profession. For Kurdish journalists, these dangers are magnified several times over.

To illustrate, if we consider journalism in its broader sense, we see that Persian-speaking Iranian journalists abroad have built extensive lobbies and networks of material, moral, political, and economic support. This provides them with a degree of social security and financial stability that leaves them with far fewer worries compared to their Kurdish counterparts. This disparity exists even though Kurdish journalists have consistently been at the forefront of truth-telling and resistance against oppressive and unjust rule in Iran. Despite the high price they have paid, the major Iranian media outlets operating abroad view Kurdish journalists and media professionals with suspicion. There is an unwritten agreement that a Kurdish journalist must, from the outset, swear allegiance to the “motherland” of Iran and turn their back on the dream of Kurdish nationalism. This is but one of the many professional challenges a Kurd faces in the field of media.

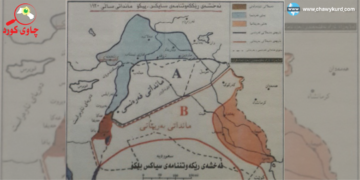

The experiences of dozens of Kurdish journalists who have worked with these external Persian-language channels and websites tell a complex and sorrowful story of the Kurdish condition. Faced with this perilous equation, it is imperative that we, as Kurds, develop strategic plans at both the institutional level—domestically and abroad—and through lobbying and networking to cultivate a free and nationalist Kurdish press. When I speak of “domestically,” I refer to the part of Kurdistan that enjoys a degree of semi-autonomy and freedom. Whether we like it or not, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, as a partial realization of the dream for 70 to 80 million Kurds, is looked upon by Kurds worldwide as a source of support. This support, both from within the region and from the diaspora, can be effective and decisive. The experience of governance in the Kurdistan Region, in terms of expanding the discourse of Kurdish journalism beyond its borders, has been commendable, if not brilliant. It serves the just cause of the Kurds and helps protect a unified identity and nation-building narrative. Nevertheless, a set of obstacles and damages remains, some of which I will highlight.

Journalists Caught Between State Pressure and the Pursuit of Truth

Journalism has always been a sacred yet perilous profession. Fundamentally, its evolution alongside modern civilization has been tied to a complex and unbreakable relationship with truth. Of course, the opposite can also be true; we can find examples of journalists whose assigned task is to distort reality and fabricate falsehoods. However, this is not typically a role a journalist actively chooses in order to disrupt social order or manipulate public opinion. Rather, throughout history, old and new powers have used various methods—intimidation, bribery, deception, and countless other tactics—to press journalists into their service, directing them toward their own interests, which rarely align with truth and justice. Meanwhile, in many countries, especially underdeveloped ones, the journalist has no one to rely on but themselves and their shadow. It is just them and their camera, pen, or phone—the basic tools with which they try to convey reality to the people. Yet, even a common soldier can conspire against them, assault them, and confiscate their equipment.

In our current era, where media and cameras have proliferated astonishingly, the profession of journalism persists, in new forms, in its effort to transmit truth and escape the web spun by the spiders of power. The situation for journalists has never been safe, not even in times of peace between nations. It is the journalist who takes the lead in uncovering the secrets hidden by authorities and their corrupt actors. It is a common saying that a free press is the fourth pillar of democracy. But in underdeveloped countries, do the first, second, and third pillars even exist for the fourth to stand upon? Can journalists truly shield themselves to defend the people’s rights and serve the truth? This worn-out cliché becomes an illusion, a beautiful dream we wish we had, where our humanity and our efforts for honesty were so valued that we would not shy away from threats, but instead take pride in knowing that we, as solitary journalists, have made the hearts of tyrants tremble.

In such a state, what definition fits the journalist other than powerlessness and victimhood? Despite this, journalists in many countries in the region are deprived of the most basic necessities for work and life. Yet, it is these same journalists who become a shield against bloodthirsty regimes, and they pay the price in the most horrific ways. For Kurds living under the rule of occupying powers, journalism becomes exponentially more difficult and deadly. The anxiety and danger multiply. A matter of human ethics and morals is quickly reframed as a security issue, and the ideological iron cage is prepared to justify their torture, imprisonment, and murder.