During the six hundred years of Ottoman imperial rule

Dozens of nations and religious communities suffered under the empire’s oppression. Consequently, when the Sultan’s authority over territories outside of Anatolia began to weaken—particularly at the beginning of the 19th century—movements of dissent and resistance against Ottoman oppression emerged among various nationalities. These included the Bulgarians, Greeks, Serbs, Arabs, Armenians, and Kurds. Notable early examples include the revolt of the Botan Emirate between 1842 to1847 and the uprising of Sheikh Ubeydullah Nehri in 1880-1881, etc…

Although revolutions and national uprisings continued sporadically against the Ottoman Empire until the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the outbreak of World War I in 1914—in which the Ottoman Empire was a belligerent—provided a wider scope for these nations to rise up. This was especially true after the war ended in 1918 with the defeat of the German and Ottoman Empires and the victory of the Allied Powers. During the four years of war, these Allied Powers continuously promised freedom and liberation to the nations under Ottoman rule through formal declarations.

One such example was the “Fourteen Points” announced by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson on January 8, 1918, which called for the right to self-determination for the nations under the Ottoman Empire. Specifically, Point 12 explicitly stated: “The Turkish portion of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development.” Furthermore, the Anglo-French Declaration of November 7, 1918, announced that Britain and France aimed to liberate the peoples who had long been oppressed by the Turks, enabling them to establish independent governments and states according to their own will.

When the war ended, the Kurds, like other nations, expected the Allies to fulfill their promises. Upon hearing news of the Paris Peace Conference, the Kurds of the North (Bakur) appointed General Sharif Pasha al-Khandan as their representative to present their demands at the conference. This candidacy was supported by the Kurds of the South (Bashur) through a petition signed by Sheikh Mahmud and several other prominent figures, designating him as the representative for the people of the South as well—though that petition never reached the Kurdish representative’s hands.

The task of the Kurdish representative at the conference was extremely difficult and arduous. On one hand, the Allied Powers were busy dividing his homeland; on the other, as a representative of his nation, he lacked official status and could not attend the conference’s formal sessions. He was forced to conduct his efforts outside the conference halls, lobbying the representatives of the Allied Powers to establish a Kurdish state in accordance with their promises. Additionally, he submitted two memorandums to the conference and established contact with other delegations, notably the Armenian representative, with whom he signed an agreement in the interest of both parties.

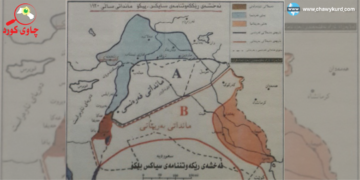

The result of these efforts was that the Allies decided to create a state for the Kurds and one for the Armenians in the Treaty of Sèvres, signed on August 10, 1920, between the defeated Ottoman state and the Allies. However, due to the success of the Turkish Kemalists on the Greek front, new shifts on the international stage after the war, and the shifting interests of the Allies, the Treaty of Sèvres was never implemented. Instead, another treaty was signed between Turkey and the Allies called the Treaty of Lausanne on July 24, 1923. This new treaty completely nullified the Treaty of Sèvres. It not only buried the idea of establishing a Kurdish state but also made no mention of the existence of the Kurds or their rights as a national minority in Turkey—unlike religious minorities, whose existence and rights were recognized.

As a result of this treaty, the Mosul Vilayet, a Kurdish-populated province, was annexed to Iraq without any guarantees for Kurdish rights within the new state. In other words, the Allied Powers not only failed to fulfill their promises to the Kurds but also partitioned Ottoman Kurdistan and placed it once again under the yoke of the Kemalists in Turkey and the Arabs in Iraq and Syria.

While the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 between the Ottoman and Safavid Empires had divided Kurdistan into two parts, the Treaty of Lausanne divided it into four parts, distributing it among Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria, without securing Kurdish national rights within any of these states. On the contrary, the Kurds in all these countries faced policies of genocide and assimilation. This situation caused Kurdish national sentiment to grow and spread as Kurds sought to define a path for struggle to escape the conditions imposed by Britain and France. Consequently, several uprisings and revolutions broke out across Kurdistan against the British, the French, and the states among which the Kurds had been divided.

Kurdish struggles for independence and the establishment of political and social organizations existed even before WWI. Examples include the Kurdish Society for Advancement and Progress (1908), the Society for the Dissemination of Kurdish Education (1908), the Hevi Society (1910), and the Jihandayi Society. After the war, the spread of nationalist thought led to further consolidation, notably through the Kurdish Society for the Advancement of Kurdistan (Taali), founded on November 19, 1917, in Istanbul. This organization demanded the independence and liberation of Kurdistan based on Wilson’s principles. They published a magazine called Jin (Life) as their official organ.

Other organizations founded in Istanbul during 1918 and 1919 included the Kurdish National Organization, the Kurdish Social Organization Society, and the Kurdish Women’s Advancement Society. The Society for Kurdish Independence, founded in 1918, was particularly significant, struggling for the unity and independence of Kurdistan. Its branches in Cairo and Istanbul sent numerous memorandums to the Allied Powers during the Paris Peace Conference. In 1921, they sent a delegation to Percy Cox in Baghdad, the British High Commissioner, seeking British support for a Kurdish state.

The influence of these organizations contributed to the Sheikh Said Piran rebellion in 1925 against the Kemalist regime, which was ultimately suppressed, leading to the execution of its leaders. Soon after, in 1927, with the support of the Khoybun (Xoybûn) Society, the Ararat (Agri) rebellion broke out, led by Ihsan Nuri Pasha until 1930. Persistent Kemalist oppression led to further resistance, such as the Dersim rebellion, which continued until 1939.

Western Kurds (Rojava) also struggled alongside other parts for independence. In 1927, they founded the Khoybun Society, which published the Hawar and Ronahi magazines. These publications were instrumental in spreading nationalist thought across all four parts of Kurdistan.

In Southern Kurdistan (Bashur), following the British arrival, Kurds demanded the fulfillment of Allied promises. Uprisings against British rule began even before the establishment of the Iraqi state, led by Sheikh Mahmud, who had been promised the title of Ruler/King of Kurdistan. Later, Kurdish resistance continued against the British and the Iraqi state until Iraq joined the League of Nations in 1932. Subsequently, the Barzan revolts began in the early 1930s and continued until 1947. During Sheikh Mahmud’s era, several newspapers with political and social character were published, such as Bangi Kurdistan (1922), Rozhi Kurdistan (1922), Bangi Haq (1923), and Umedi Istiqlal (1923), followed by Zhianawa (1924), Zhian (1926), Zari Kirmanji (1926), and later Jin and Galawezh in 1939.

In Eastern Kurdistan (Rojhelat), Simko Shikak was in constant struggle from the early 1910s until 1930 for Kurdish liberation against the Qajars and later Reza Shah Pahlavi. Following Simko’s era, the Kurdish Freedom-Lovers Party was founded in 1939, followed by the Society for the Resurrection of the Kurds (JK) in 1942 and the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP-I) in 1946.

Reflecting on the post-WWI situation, it is clear that the promises made by the Allied Powers to nations under Ottoman rule significantly influenced the growth of Kurdish nationalist thought. However, the outcome was disastrous for the Kurds due to the Treaty of Lausanne, which partitioned Kurdistan into four and imprisoned each part within a chauvinistic state that denied Kurdish existence and rights. This betrayal served as the catalyst for the Kurdish revolutions throughout the 20th century. Today, the Kurdish issue remains a primary challenge in the Middle East, as none of the states where Kurds were divided enjoy true peace or stability, largely due to the unjust imperialist policies of the early 20th century.